Pawntrophology

NEA defunding, Brodernism, Alex Perez and how translated literature became a pawn

The first thing you need to know about the pushback against translated literature is that this is just beef between a bunch of men. I would call them bros, but someone else already did. Federico Perelmuter coined the term Brodernism to describe a trend that’s taken hold in the American Republic of Letters: male book critics propping up difficult, long works of fiction. It was the bro that was heard around the literary world. It was very hurtful. The second thing you need to know about the pushback against translated literature is that at some point, things escalated into something serious, and the literary men were trapped yelling at each other on X/Twitter, making severe accusations while the funds slipped away from books and toward the 250th anniversary of American independence, fostering AI competence, MAHA, the military, houses of worship, skilled trade jobs and making the District of Columbia safe and beautiful.

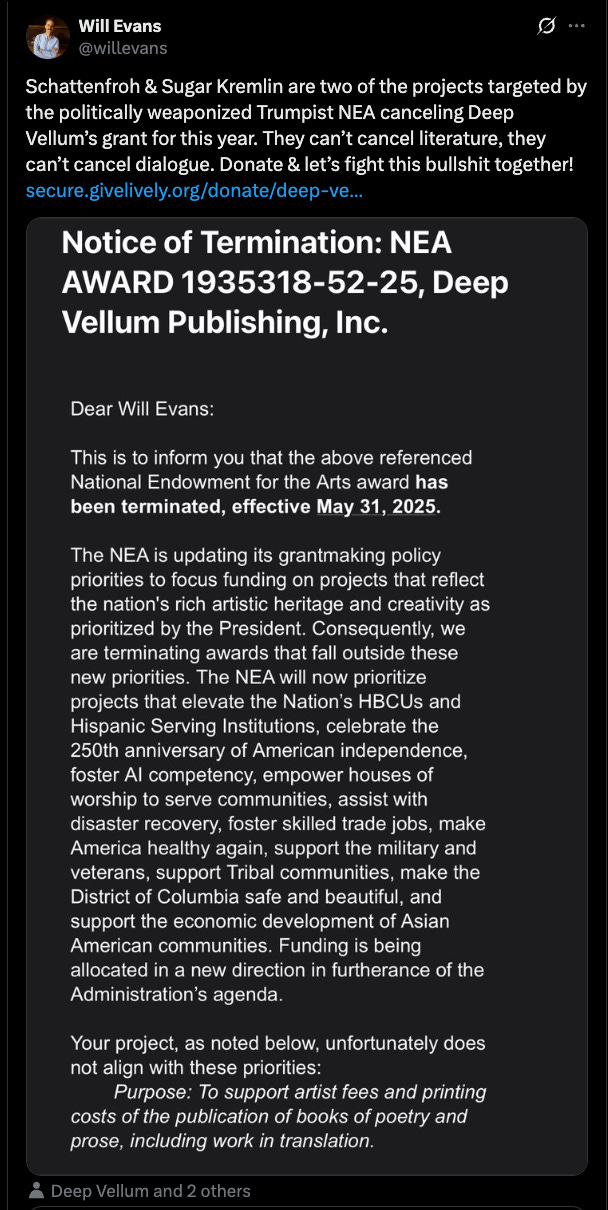

Everyone saw it coming. If they didn’t, they should have. The inauguration brought together the CEOs of the largest tech companies in the country, and immediately after the inauguration, their companies announced cuts to the DEI programs (a friend of mine told me the language at her company was “sunsetting”). I saw it coming, but maybe I’m more stressed out about resources because I worked in reproductive health advocacy after the financial crash of 2008, and have seen grants slashed by the order of millions. In any case, on May 2nd, the National Endowment for the Arts sent out letters to grantees announcing that their funding would be terminated starting May 31, 2025. According to a conversation organized by Post, 45 of the 51 literary grantees confirmed they got an email/letter. Two of the publishers that have championed Romanian literature in translation (Will Evans of Deep Vellum and Chad W. Post of Open Letter, Dalkey Archive) have received these letters. The American edition of Solenoid would have been unlikely without support from the NEA, which offered Sean Cotter a translation fellowship (the second ever for a Romanian-language book).

Tweeting in support of the organizations that lost their grants and donating began immediately. But on some corners of the internet and Substack (and quite possibly in many private WhatsApp groups), some people were gleeful. Schadenfreude, the German word that we use to describe TFW we enjoy the troubles of others, doesn’t feel enough to convey the intensity of this glee, but it’ll have to do. Why? Because it’s hard to get money for literature, that’s why. You need connections and privilege to break into nonprofit publishing, just like in big publishing. Dan Sinykin, whose book Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature traced the origins of nonprofit publishers, argued that this sector of publishing reproduces our society’s unequal distributions just as much as conglomerate publishing does. Nonprofit presses are overwhelmingly owned by white men. Writers who are underrepresented are useful to these publishers because they come from underrepresented groups. Nonprofits escape the market, but they can’t escape funding and playing into larger power structures, “keep the right politicians and wealthy people happy.”

The thing is, politicians and wealthy people are not happy right now because of the stock market and tariffs. Democrat politicians, in particular, are not happy because they lost the presidency following a massive cover-up of Biden’s health woes. Now they need to choose a new direction that doesn’t revolve around Charli XCX's hit brat or a partnership with Liz Cheney (that didn’t work lol). They are not happy because there is a lot of work to be done now, and chanting “We will win!” won’t do.

Even the politicians and wealthy people who are winning are not happy. Elon Musk, (ex?) head of DOGE, struggled with blowback against Tesla, whose stock dropped 50% since January when he joined the administration to lead DOGE. Though it’s picked up steam in the past month, investing advice is still reserved (“Ultimately, investing in a stock like Tesla requires a strong stomach and a long-term horizon.”). Musk also got in a very public disagreement with Nicolai Tangen, the CEO of the Norwegian wealth fund (who voted against Musk's $56 B package). Have you met rich people who did not get the money they thought they would? Speaking of which, Jeff Bezos, the former CEO of Amazon, is also not happy. Yes, he is in Nice on his yacht, and he is soon to marry a woman he sent into space. But! His competitor SpaceX and Starlink got 2x the amount of government $$$ that his space company Blue Origin did. Not happy.

Right now, Amazon is still helping support literary projects. In 2024, Amazon Literary Partnership funded 93 organizations (including Deep Vellum, the largest publisher of literature in translation, projects like Girls Write Now, magazines like Lambda Literary, or writing colonies like MacDowell). But in January, Amazon halted its DEI initiatives, so I do wonder how that will play out with Amazon Literary Partnership’s mission “to fund organizations working to champion diverse, marginalized, and underrepresented authors and storytellers.” We will find out in June more about this year’s grantee cohort and maybe any revised application guidelines.

Long before the funding was redirected toward all the beautiful American projects, some people in the literary world started to turn on translated literature.

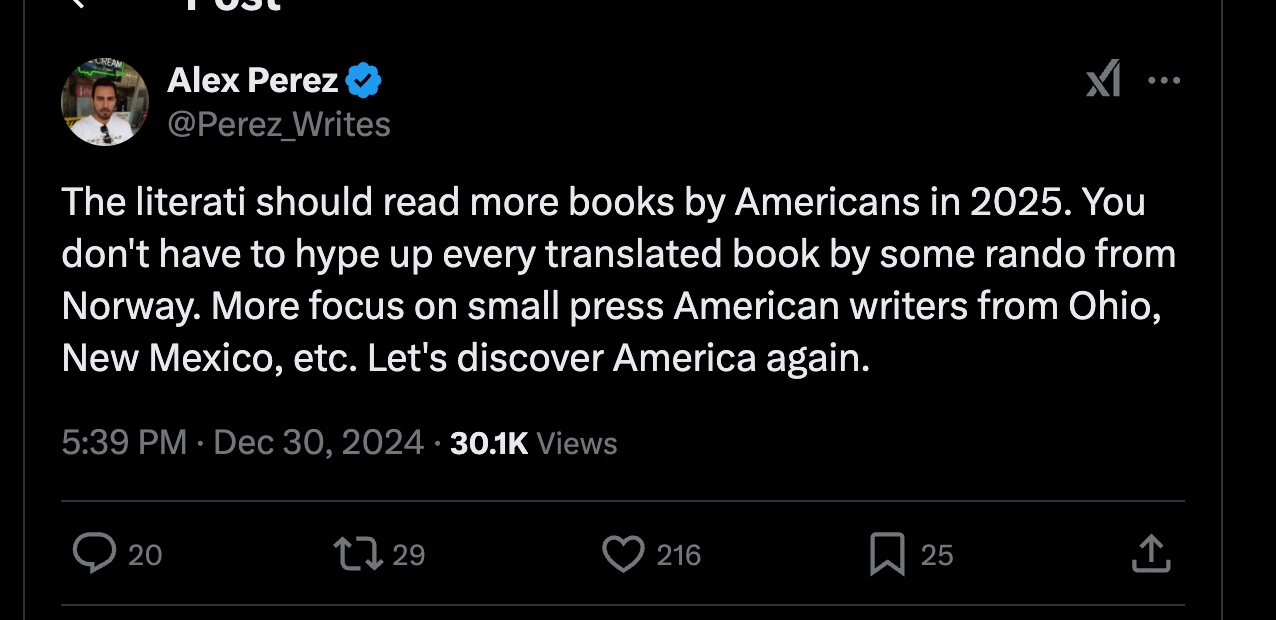

In 2022, Alex Perez, a Cuban-American writer, wrote about the problematic literary men in translation, male authors who got published and praised despite the misogynistic stuff in their books: “With foreign writers, it’s a different story. Like Bolaño, the French novelist Michel Houellebecq and his Norwegian contemporary Karl Ove Knausgård have epitomised the rise of the literary noble savage. These two have built careers on “problematic” subject matter that would get an American-born writer cancelled. Why are imports allowed to thrive?” Gradually, this criticism turned into a stance that’s easy to use a branding: anti-Norway randos, let’s discover American writers.

Perez's issue isn't about literary giants like Knausgård, Houellebecq, and Bolaño—he's merely using them as convenient examples due to their race, contentious writings, or inability to respond. Instead, his frustration lies with the less-established, maybe younger foreign writers (Francesco Pacifico and Alejandro Zambra are both briefly mentioned in his article) are published and invited to parties even though they say the stuff that makes him be unpublishable and keeps him out of parties. Perez suspects (rightfully so) that these writers' success has been made possible by what has not been translated: the controversies of their lives that have remained unknown. I can’t believe I need to spell this out, but the works that aren’t aligned with the audience’s sensibilities tend to remain untranslated because the goal is to sell those books. So yes, foreign writers escape the harsh judgment typically reserved for US writers because there isn’t enough money to translate problematic works. Mircea Cartarescu is an example: his nonfiction work remains largely unpublished, and some of his more contentious takes aren’t known by his American fans.

But whose fault is it that these writers remain a mystery for the American public? It’s not like they prevented translators from translating all their work; their interviews are available on the internet and can be researched/translated. What stops Perez from writing an in-depth piece on a translated author? By all means, give every translated author the Mr. Difficult or Our Struggle treatment. I would love nothing more than to listen to American book critics analyzing all of Cartarescu’s books and personality quirks. His journals are full of stuff that would raise an eyebrow, but they’re also testaments of writing fiction that isn’t catering to the market. Perez is welcome to do this.

Like the elites he despises, Perez is choosing to save a group he perceives as useful for his brand (writers from New Mexico and Ohio, chef’s kiss). But I think the writers from New Mexico and Ohio are all good. You know who’s a writer from Ohio that’s proud of being from Ohio (“Ohio against the world)? Hanif Abdurraqib. He published with Two Dollar Radio, a small indie press from Columbus, Ohio, whose authors are widely read by the NPR, New Yorker crowd. My question is why does Dallas rub him the wrong way? Isn’t Dallas as American as it gets? Why the hate toward Deep Vellum? Perez's latest crusade to champion working-class writers is admirable, especially in the context of writers who’ve published fiction based on voyeuristic working-class stints (Adelle Waldman). But it reveals a curious alignment with the current administration's focus on revitalizing manufacturing jobs. This pursuit might be viewed as an opportunistic move, capitalizing on the growing interest in the American working class. Perhaps it's not Dallas or Deep Vellum per se, but rather the fear of competing with another champion of underrepresented voices.

Perez started his career in the public eye bashing white literary women who live in Brooklyn and wear tote bags (“These women, perhaps the least diverse collection of people on the planet, decide who is worthy or unworthy of literary representation.”) Recently he started asking how he might get a tote bag himself. As Naomi Kanakia wrote, every new administration is a time for a changing of the literary guard: “Pick one of us, turn one of us into a star.”

What I wish had happened when the Brodernism and the “stop translating Norway randos” conversations broke out? I wish one of the American editors and translators had involved someone from the countries affected by this. Romania is full of social media-savvy literary scholars, and none of them were paged to jump into this. Instead of retweeting Perez with stuff like “what is this guy’s problem” and accusing Perelmuter (the author of the Brodernism article) that he personally influenced the defunding of the NEA, they could have organized a call between, say, Mihai Iovanel and Perelmuter on the issue of Brodernism.

The loss of NEA grants and the business troubles of the rich Western men will make translated literature more dependent on funding from the international government translation agencies. The problem is that those countries also elected more right-wing politicians (including Norway and South Korea, the powerhouses of translated literature). Despite potential concerns or qualms about these agencies, American publishers may hesitate to challenge them publicly due to their financial dependence on these institutions. It is a cursed scenario for authors, translators, and editors in those countries.

Don’t wait for PEN to invite you to New York for a night of multiculturalism celebration. That won’t get your book translated or sold. Even Mircea Cartarescu had to wait one full decade after his PEN visit (plus, no one will replicate his career path). If you’re an author, translator, and editor, you should aim to build an international following. When these institutions get in the way of your translation project, it’s helpful to be in a position to expose these problems. The Romanian Cultural Institute will not suffer because it didn’t translate a book. If you want your book out there, figure out how to create the connections that give them no other option but to translate your book. Take a cue from Anton Hur Take and his blow-up with LTI Korea. (Hur was also vocal when a US publisher who got a grant from LTI Korea for a series of translations did a bad job at choosing the cover art.)

I am so sorry but there is no one coming to save you and the best you can hope for is someone will say something stupid about translations to let you @ them.