#3 Work-life comrades

A slim volume of private dystopias revisits the decades when the Romanian communist regime aimed to build a gender-equal, gender-neutral world.

In January, 1990 when my classmates and I returned from our winter break, we were instructed to stop calling our teacher tovarașa (comrade). Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime had been toppled during the break; he and his wife Elena had been shot dead on Christmas day. We were told communism had been a lie.

Tovarașe de drum (2008) is an anthology of essays in which seventeen women writers unspool the lies at the core of a regime that fashioned itself as a utopia of gender equality. The title could be translated as Journey Comrades, a riff on the official communist party dogma which posited that women and men were “work and life comrades” but the book has not been translated into English. Published in 2008, at the end of a lengthy and jading so-called transition period, in the afterglow of Romania’s prized acceptance into the European Union, the book is written from a bearable remove from both the past and the future. This was the calm after the storm, a period marked by international political triumph and economic growth. On the World Bank GDP per capita growth chart, one can see what a big wave was looming; the financial crash that would come in 2009 was going to trigger the largest drop in the country’s GDP per capita since 1997 and the mass migration of Romanian women to the West.

None of the ordeals revealed by the authors are new news for those even remotely familiar with Romanian communism. People were starving, they were freezing, they were very poor. What may be novel is how they evaded these sentences. At the Black Sea with her best friend, an author remembers coming up with an eccentric alternative to hunger: she sprinkles Ness instant coffee powder on toast. “We had a can so why not. It tasted a little salty, kind of like peanut butter though I didn’t know that at the time.” To avoid being reported to the secret police by their downstairs neighbor, one author’s father discards the remnants of a packet received from a relative in Israel—an empty coffee can, a Toblerone chocolate bar wrapper, chewing gum packaging—in a public park, not the building’s trash container. A lot harder to read are the sections that deal with the ban on contraception and abortion: “the preferred method of causing a spontaneous miscarriage was placing a pillow on top of the abdomen and having someone punch you repeatedly” or “jumping (preferably from a tall wardrobe).” That anyone came out live is a miracle.

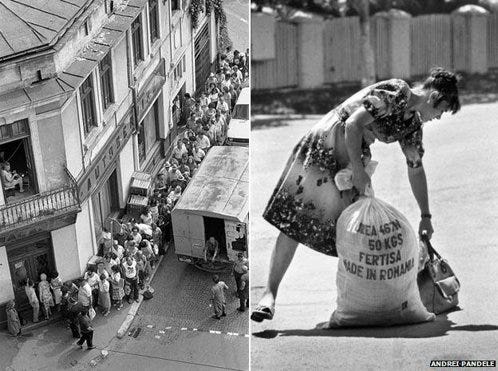

To the extent that what is revealed is surprising, it is because it throws the present day into a disquieting light. “All you could find were uniforms,” writes one author. “For a few seasons, we were sold the so-called dry shampoo that replaced not only the actual shampoo but the need to use water,” she sneers. “We used to laugh at the tens if not hundreds of people waiting in line to buy broth bones,” writes another. Coming upon these sentences, I had a feeling that the next dystopia will be different from the one imagined by Margaret Atwood in Handmaid's Tale (which was partly inspired by Ceaușescu's pro-natalist Decree 770). It doesn’t have to be the handmaid uniform. It can be one of the countless we are invited to buy: the everyday uniform, the January uniform, the new work uniform, the new cozy-at-home uniform, the new summer uniform, the summer-after-summer uniform. Aren’t products like dry shampoo and bone broth, artifacts of earlier eras when water and utensils were not available, dress rehearsal for a time when the price of water futures will go up?

At its strongest, the book succeeds to deliver a sketch theory of Romanian womanhood under communism. The first essay, Sarsanela (The Tote Bag), written by Adriana Babeți, is a communist-era hunter-gatherer tale that centers the gatherers, the “women-horse” always scavenging and lugging food “without hurt or heroism.” From a young age, Babeți decides that she will become a woman-horse. All around her women hoist and haul every imaginable thing: buckets of water, sacks of corn or sacks flour, crates of jam, barrels of brandy, wicker baskets crammed with vegetables. They lug firewood, potatoes or coals in shoddy metal carts. She adds rocks to her kindergarten lunchbox but doesn’t become a woman-horse in earnest until after she finishes college. Between these two moments, a new generation of carrier receptacles revolutionizes the carrying game and the style of these women. Unlike the tote bags and wicker baskets of yore, bulky and non-ergonomic, the modern vessels are made of synthetic fibers and plastic. They are bright, light accoutrements that can be snuck into a purse, matched to one’s shoes or scarf.

In the 1980s, forced to procure food, wood and coals on the black market, the women-horse up their game once more: they to do their hauling at night to avoid being reported to the secret police. One night, as Babeți is balancing two bags (filled with apples, pickles, and miscellanea from Germany) in one hand and one carton of eggs in the other, she falls into an unmarked ditch that’s roughly two meters deep but does not let go of the bags or the egg carton. They are “fresh eggs from Ciacova” and they are part of a larger scheme. (Under the 1985 “scientific diet” Romanians were allowed one egg every three days.) She is rescued by a blind man and continues on into the night, knees a little bloody, spirit shaken but fine otherwise. She trades the eggs and the apples for half a slaughtered pig which she carries home high above her head like a “gladiator.”

Whether Babeți winks at Elizabeth Fisher’s Carrier Bag theory of human evolution, whose chief claim is that “...the earliest cultural inventions must have been a container to hold gathered products and some kind of sling or net carrier” is difficult to tell. I am, however, certain that she puts a weapon in the hands of women. It is stylish, not sharp like the “the sticks and spears and swords” but they are cunning at wielding it to fight hunger and the cold. As Ursula K. LeGuin points out, the carrier receptacle is “the tool that brings energy home.” Why slaughter an animal if you can’t bring it home?

A woman-horse is not a nymph. “Younger women like my mom preferred their chic tote bags even if this required multiple trips to the Lahovary market.” writes Babeți. In Eu, una, n-am suferit! (I, for one, have not suffered!) Ioana Ocneanu-Thiery writes “Since we were unaware that losing our femininity was supposed to count as a major gain for women, we worked hard to stay beautiful.” Their hearts and eyes are set on the oppressive feminine artifacts that the Western second-wave feminists threw into the trash can: bras, high-heels, makeup, hairspray, perfume. In Halatul Veronicai (Veronica’s Robe), Anamaria Beligan writes about the struggle to procure sexy underwear of the sort seen in movies which led, at the very best, to undergarments from Prisunic, a French chain store whose tagline was "Beauty for the price of ugliness". “Even if I darn my socks and underwear (I can’t replace them because there are any in the stores), I still care how I look. Sometimes I even wear a necklace.” writes Adriana Bittel in Servus, Reghina (Hello, Reghina). In Atunci am invatat sa renunt (That’s when I learned to give up), Gertrud B., a German ethnic teacher recalls clamoring for nylons and boots (“a dream of mine that came true later”). A pair of nylons costs as much as a pair of boots. Neither is available. There are lines to get nylons mended. In Din umbra unui viitor luminos (From the shade of a bright future) Sandra Cordoș makes a list of things one could not find: matchsticks, lighters, lipstick, soap, shampoo. In HoRor! Cool! Simona Popescu writes about the lack of perfumes which led to the habit of putting bars of soap between one’s clothes. Lux, Rexona, Polish soaps, green apple scented soaps from Bulgaria. In A-ha! Otilia Vieru-Baraboi writes about the twinge of anxiety that accompanied the imminent emptying of an Impulse deodorant spray. She collects the empty spray cans.

At its weakest, the book comes across as uncritical of race and class relations. Roma women show up here and there: as nannies who cannot meet the mandates of a mom hell bent on boiling diapers, as voices in the food lines or in hospital beds. The workers who controlled the means of production have not been forgiven. Communism was anti-intellectualist: workers in restaurants and factories were seen as doing the most productive work in the society and given access to food ahead of intellectuals like the authors of the book. They had to bow to the authority of these workers in return for fresh chickens, butter, kashkaval cheese, superior meat trimmings, etc. Even though after 1989, most of these authors received grants, residencies or professorships in Western Europe, while most workers descended into financial ruin, they continue to portray themselves as victims. The mineriads of the 1990s did not help heal the relations between these classes: between January and June 1990 the miners from Jiu Valley came to Bucharest, at the invitation of the former president Ion Iliescu, and roughed up students and other protesters who were asking for Iliescu’s resignation. But then again, at the time the book was published the mineriads were part of the past.

It occurs to me while reading a book by another Patricia at the same time I read this book that I “would have preferred another lineage—aviatrixes, jazz kittens, international spies.” I would have preferred the women who’ve been put on the pedestal of feminist history but I will make do with the women-horse. After all, haven’t I pushed an IKEA Tarva dresser in a groceries cart from Red Hook to South Park Slope? Haven’t I carried the tightly packed untreated pine wood planks up two flights of stairs like a gladiator? Yes, I have.

ROMANIAN BOOKS ELSEWHERE

Magda Cârneci’s FEM in LARB reviewed by Alta Ifland.

References:

Ghita, Ina. Altering Cooking and Eating Habits during the Romanian Communist Regime by Using Cookbooks: A Digital History Project, Encounters in Theory and History of Education Vol. 19, 2018, 141-162.

Le Guin, K. Ursula. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1986. Anarchist Library.

Miroiu, Mihaela. ‘Not the Right Moment!’ Women and the Politics of Endless Delay in Romania, Women's History Review, 2010, 19:4, 575-593, DOI: 10.1080/09612025.2010.502402